A few weeks ago I was asked to have a look at a system. I can’t really share which system but it is not really important to the story. This system is not that unique in any specific way. Users can register an account. Users can login and do things. All the things one would expect from a website that offers a service these days. I must say the people running the website even had things pretty well setup. There even was some monitoring. Now normally this system just runs. Developers develop new features. Every once in a while something breaks.

But on a given afternoon something strange started happening. Their monitoring alerted them that there was something going on. The error rate on their login endpoint was trough the roof. That is to say 99.x% of the requests to that endpoint resulted in a 403 or a 429. Something was clearly up.

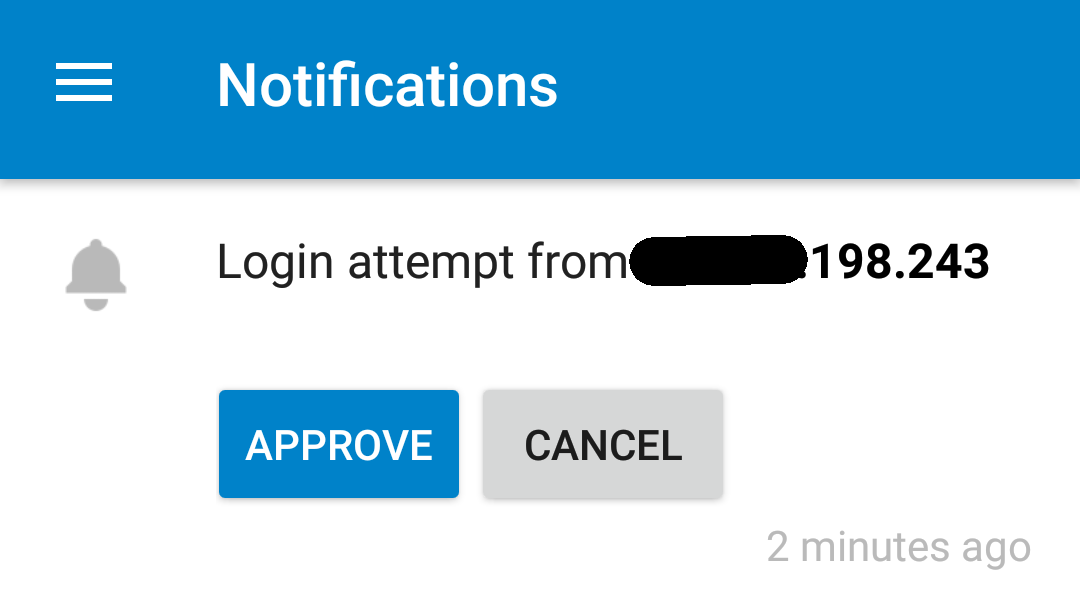

As it seemed that the rate limiting was nicely kicking in they did not worry to much. On top of that most of their users have Multi Factor Authentication enabled. But still it got them wondering. What was going on. As the requests kept coming in we decided to start collecting some data.

The first thing we wanted to know was how many of the users that tried to login actually had an account on the system. This was just a very simple extra lookup on the endpoint. After having this run for about an hour it turned out practically none. Of all the failed login requests only 0.01% (rounded up) had an account on the system. This in itself is already strange. And it started to smell like credential stuffing.

To quote wikipedia:

Credential stuffing is a type of cyberattack in which the attacker collects stolen account credentials, typically consisting of lists of usernames and/or email addresses and the corresponding passwords (often from a data breach), and then uses the credentials to gain unauthorised access to user accounts on other systems through large-scale automated login requests directed against a web application.

Now we had the first part of the credentials (email addresses) but what about the second part. The passwords? Well for that we started adding a tiny bit more code but still just a few lines. For failed logins we also looked up if the password appeared in the Pwned Password lis of haveibeenpwned.com. This got deployed and we let it again ran for a little while. This showed that 99.98% of passwords used in failed login attempts were already known. Now this is not definitive proof. But if it looks, swims and quacks like a credential stuffing attack it probably is a credential stuffing attack. In any case it gave us enough confidence to conclude that somebody managed to get ahold of some data breach (most likely a breach already in haveibeenpwned) and was performing a credentials stuffing attack against the service.

After all this fun we had what we needed to hand the issue over. And they started to block IP addresses more aggressively if they did a lot of failed login requests with distinct usernames and >90% of the used passwords appearing in haveibeenpwned. This brought down the error rate quite fast. The attack went on for a while longer but eventually stopped.

This experience got me thinking that there might be something here where we could utilise such information better. A system where such statistics are collected and stored could make use of this. By lowering the rate limit for IPs that make request that look like credential stuffing attacks for example. Or making it visible for the administrators running the instance how many of the login requests fail or exhibit this behavior. It for sure is something I’m going to think more about more.